After lunch on Sunday 16 October 1988, Gerard, who was new, said a fair bit. It was very positive, even flattering to the group, but I don’t think it calls for report. However, some of Mr Adie’s response was interesting: “Intentional suffering, particularly its part in the construction of the universe, as put down in “The Holy Planet Purgatory” may be the most difficult concept of all to approach. But if you try to think of the Absolute, or of the Creator, one is quickly out of one’s depth.”

“I remember very early in the work I had an appointment to meet somebody in London. The question of the Absolute and the laws had recently been discussed, and I was trying hard to approach the laws and the Absolute. One of the elder people in the work happen to come by and ask me what was I occupied by? I said I was trying to think about the Absolute. He said: “Oh, you can’t do that.”

“I wasn’t particularly abashed. I accepted it in a way, but in another way, I was not so sure, because I had started to find something. I now understand that it depends upon which mind one uses, and whether I have a need to understand. If there is something I wish to understand, the question of suffering, or of justice, I can come to a point where the Absolute is of great practical importance: it makes all the difference between despair and hope. And then I see that, in my being, I need not some plausible chain of logic, but a raising in my intellect and my feeling. I can then see that for a change in state what I need is not ordinary logic but contemplation. Not an answer from the mind alone, but from three centres.”

“If I try with the mind alone, it’s the furthest thing is it not? The Creator, the total cosmos is everything. But the concept of the Creator still means something. However, even that will be quite out of one’s reach, will disappear, if I am in a tense state, or I am negative, afraid, or anything like that.”

“If I am negative, then I don’t have this question in the same way at all, because the very question I have indicates a certain contact with it. I cannot ask a question about something which hasn’t got some reality for me. My question makes that essential. But what is the contact: how deep, how sustained? Does it perplex me in the head or does it touch my feeling of myself?”

After a little pause, Mr Adie added: “I had been pondering asking everybody to accept a task, and that is that before going to bed tonight to read we again this particular reading. It is only a matter of six pages. There’s so much in it that one would have missed, woven in. Sometimes the important concepts are apparent, but sometimes they are barely visible at all. If you read it and try to observe yourself reading it, you may not lose all of what is there. As Gurdjieff said, it is the heart of the work. Good. It is good hearing that you as a newcomer find quickly that there is work here.”

The next question was from Grover: “The attempts to make the ten-minute stops were again felt today. They brought in a way, three different things. One was, there were a few moments during the day when there was a very simple feeling of, I’m alive. Just a simple as that. Then. there were also several very, very clear impressions of myself being automatic.”

“Yes,” said Mr Adie, “but let us just take your first example. I felt there was something in that. I just want to wait one second, to see what you said, to understand in myself what you had said, and what it contained.”

After a short pause, Mr Adie continued: “You saw the simple fact that there is life. I have to stop and give place for it, otherwise I’m engaged. I’m engaged in listening, you see, but if I really hear what you say, then I have to allow a place for it. Is it not so?

“Yes,” said Grover: “as soon as you interrupted me it came back, and there was a feeling that it was more than what I had first thought.”

“Yes, yes. It’s a substance that I can’t describe, a live substance. And the second thing was seeing your mechanical manifestations?”

“These impressions of being automatic,” said Grover, “having this feeling of just knowing my state just plodding along, automatic, dead, no life there.”

“Of course,” replied Mr Adie: “life has started to appear in order to make that observation, or if you like, by reason of it. By the very fact that I see there is no life here, life has already come – at least in that form. I observe, as both an observer and an observed, so that is life. If I could only have that in a very simple form, this automatic functioning would not cause me to lose my consciousness. In other words, your observation puts a maximum on observation, because an observation is contact with that life, and without that seeing, my life is a sort of an unattached force. Is it going to permit me to be in the right place, or is it just going to disappear?”

“So, every moment of observation has a value – whatever I observe about myself. I might observe that I’m wretched or resentful; it doesn’t matter. There’s this thing, this part that I miss continually. I sense the lack of a conscious part, because there is a conscious part there, albeit very small.”

“It would be a very important, just as we are now at this moment, to realise that any observation I make and notice in that way gives me a chance. It’s the beginning of consciousness. It’s the beginning of it for development. It’s a witness to the fact that in a minute degree it’s already there. Sometimes it’s very difficult, I’ve got a grudge, or something is wrong, and it seems impossible, but it isn’t. It’s never impossible. For us I think “impossible” is the worst word in the whole gamut, it’s the biggest denial. Well, one has got to have words of every kind, wonderful words, but I think “impossible” is the Hasnamuss of words. What courage can it give? What despair can it annihilate?”

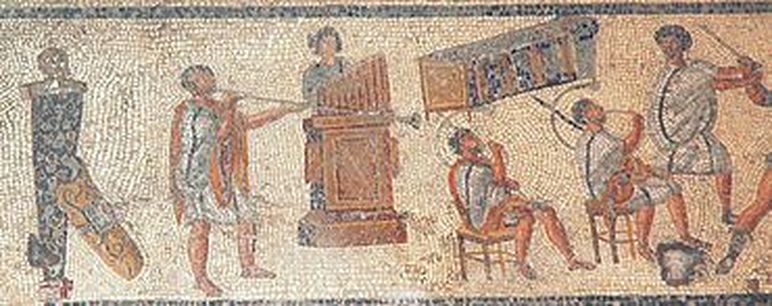

Grover added: “A third thing was the way the job went; almost every day at the end of a working day I feel dissatisfied, that there wasn’t enough done. But today is one of the few days that I feel quite satisfied. I was late before tea because I spent a bit of time putting in one stone to finish off the whole section.”

“A bit of protection and a conclusion,” said Mr Adie.

“Yes,” agreed Grover, “it just seemed there was enough push there. In the past, too much of it has led to hurry and frustration. But today we kept the job moving along at a better speed, and so there was a push, but there was reason there as well, not letting it go too much. There was an impression of more sanity or balance.”

“So you would have seen people working,” agreed Mr Adie, “a picture of work. All these elements there, a push, sanity, balance. That’s work.”

Have you ever thought of publishing George Adie’s transcripts? They’re incredibly helpful and very few people are aware of them. It would be an invaluable service now and for future generations.

Thanks. He would be gratified. Well, there is the book, “George Adie: A Gurdjieff Pupil” available from By the Way Books. Also, I am speaking to some others of their former pupils about a joint effort concerning Mrs Adie. Even if that does not go ahead, the Bennett volume is my present priority. Perhaps when that is done …