New words are marks left by the visit of a mind. A particular thought or feeling, some instinctive or physical reaction expresses itself, and impress itself upon us enough for someone to coin a new word. The same is true of new usages, or changes in usage. Sometimes a new or newly favoured word or a phrase actually marks the laziness of a mind: e.g. the habit of using “like” as a filler or to avoid being precise. But that is, nonetheless, the mark left by that mind. It has a significance.

I am sure we can all vividly remember occasions where we have been faced with some conundrum. Perhaps we were trying to formulate an aim which meant something to us. We had an distinct feeling which we could not articulate, and we had to work to find words which corresponded. We gave the matter some connected thought, and came up with a formulation which helped us.

On those occasions, the word or phrase is like a stepping stone placed in a stream. It is invaluable: we could not or would not cross without it. I remember the creek at Rydalmere. In some places there was a stepping stone or two, or a makeshift bridge. They were like magnets. We were drawn to them: small children leap around at such points, they cross, then they recross, then cross again. I still recall one occasion when a stepping stone had been moved. I was about thirteen. I was trying, without much luck, to replace it. Suddenly, I realised, I did not have the replace that stone there. I could find another spot, and devise something there. And I did. A little further up, off the path, was a better place. In time, a path was beaten by reference to that stepping stone.

The analogy with words does not have to be laboured. This raises the question, if words result from the notice of a mind, how conscious is the culture we produce, and the language we speak?

Let me start indirectly. Recently, some of us tried to observe the sensation of the mouth, as a sort of support for our self-observation and self-remembering. I recall once speaking to Mr Adie about a tension I had noticed in the part of the face above the lips. In trying to describe the sensation, I said that it was “the lower visor,” and held my right hand six inches away from and directly before my lips.

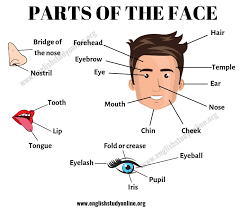

Mr Adie knew what I meant at once, and pointed out to me the word “mouth” has several meanings, but there is no organ or member which is the mouth: the “mouth” is an abstraction. It is not the same sort of word as “ear” or “nose.” We speak of the mouth, but in fact there are lips (the “corners of the mouth” are where the lips meet), there are the cheeks and the oral cavity with its tongue, teeth and palates. The more one ponders this, the more one studies the mouth, the more detailed one’s understanding of the marvel of it all: the different types of taste cells, the saliva system, the inner cheeks. It is far more interesting and endlessly more practical than the things we amuse ourselves with. If we had even half a measure of sanity, the t.v. would be filled with documentaries on the human body, and those manufactured sitcoms, titillating at best, would go the way of pink toffee-coated peanuts.

There are too few words in English for parts of the face, especially for the areas of the front and sides of the face. Some of these regions are quite expressive, e.g. the creases which descend from the nostrils and curve down to the lips. Not only the creases themselves, which it seems plastic surgeons call “laugh lines,” but also the parts of the face between them are often animated. Although we have no word for them, at least none in common usage, we do notice those unnamed features. But have our minds visited this feature long enough to find a word for it? Not unless we are plastic surgeons.

The “mouth” is a section of the face between the head and the throat, indicated by the jaws, lips, and other organs and members. “Mouth” will usually, I think, conjure up ideas of the oral cavity, or of the two lips. It is particularly associated with the two functions of speaking and eating. We say someone has a “big mouth” if they talk to excess. The slang word “gob” will only refer to the orifice, but it cannot be used at all decorously for the mouth. I am hard pressed to think of another such word.

The deeper significance is that our language and our speech are conducted almost entirely by unexamined association. That is, our speech is not formulated with any great degree of consciousness. So, what do we mean by “mouth”? When we were speaking among ourselves about what we had found when observing the mouth, there were many good insights. Yet, we were all the time shifting from one meaning of “mouth” to another, without being aware of it. I find that when we make the effort to be more precise in our observations, the impression of our observations, and hence the energy they supply, goes deeper.

That brings me to words for speech. There are differences in nuance between words like “talk” and “speak.” For instance, compare “He talks a lot” and “he speaks a lot.” Although the two words are often used indiscriminately, I do not think they are always inter-changeable. Since “speak” has a connotation of intention which “talk” does not, to say “he speaks a lot” makes him sound as if he travels around delivering lectures. If I was describing a motor-mouth, I would definitely say “he talks a lot” and not “he speaks a lot.” We say that a person “speaks up,” not that he “talks up.” We say that you “speak your mind.” If I said you “talk your mind” it would suggest that what you had to say came out like a recording. The phrase is “speak well of,” not “talk well of,” showing once more how “speak” is more naturally used for intentional speech.

But why do we not have a specific word for “speaking consciously”? Surely it means that the concept of speaking consciously is not present in the culture.

To be continued, Joseph Azize, 28 August 2020

This is so helpful. I was in a meeting yesterday where we were practicing inquiry and one person asked, “why do we have to use words?” and of course, it’s fine to paint, dance, sing or sound things, but somehow I just knew that it was important to also try to find words and speak consciously about our experiences, but I was at a loss for how to really explain this. The stepping stones image is so vital to what it is that came up in my mind – how to cross from unconscious to conscious, how to express in that in-between space . . . . I will be reading this again. Thank you.