These exchanges from the Sunday of 13 November 1988 are of some interest, not least because Mr Adie speaks of our needing many impressions, even the impression of fatigue. The morning address was excellent. I am saving it for 29 July, together with some of the questions. But these other exchanges are also of value.

Part One

In the first of them, Penny stated that during the morning she had realised that she was exhausted. Her aim had been to work against dreaming by working quickly, but she found that she had been using tension to go quickly. She relaxed, and that helped, but the struggle between tensing and relaxing went on all morning.

“So, it wasn’t all dreaming then?” asked Mr Adie. “That’s good. You see the difference. Because you had all these alternating experiences, so some of the time you knew very well that you were not dreaming, not to the normal extent, anyway. You have more facts. There is no mistake about such an experience.”

Then Penny asked whether the dreaming might not even be a way of relaxing tension?

“No,” replied Mr Adie, “The relaxation we want is conscious. Don’t muddle things up. You can use the dreaming to remind you to relax, just I mentioned at breakfast about using violent negative emotions for transformation. If you notice the tension, you have a reminder. Alright, so then you need to take measures. In the case of the big negative emotion, you may notice it, but it doesn’t stop, so you then have to utilise that for the work.”

“Always, if I notice, I will find material there, material for consciousness. If you really come to think of it, you will see what the grace of life is, that any element in you becoming aware, then there is what you need: impressions. In this case, impressions of fatigue. There are other impressions, of course, but not so many were received in this case because of the tense hurry and the considerable fatigue it produced.”

The next question was from Gerry. “The statement this morning that we could work for hours from ego really struck true with me in my normal job. Because, in my normal job that is what I do.”

“Yes,” said Mr Adie, “everybody has that. But not only in their job, also when they play, or when they’re out having a good time.”

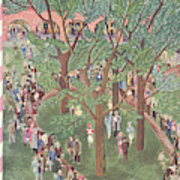

“I thought I was lucky that the job I was given is a job I normally do,” Gerry continued. “I made myself an exercise that every ten minutes I would stop for a moment. The tensions were unbelievable, and the magnetism of the job – and the thoughts “If you do this then you must do that”, and I was going to say I had to work very hard, but that is not the right expression, but just put my thought on my sensation. It was so strong, but the stop with a large number of people helped me to be a little bit in the middle, not lost, I had some sensation, and I got quite a lot of work done.”

I mention these stops in the book George Adie: A Gurdjieff Pupil in Australia. We would stop our manual work each 30 or 60 minutes, collect ourselves, turn to those we were near, and meet their gaze for just a moment, then return to our tasks.

“I also think,” continued Gerry, “that all these thoughts I had had were things I would have come to in a natural progression, so I didn’t have to be going over them in my head all the time, I would have done them anyway without going over them in words. That was interesting, because at first I thought that the thoughts were useful.”

“What were the thoughts?”

“Well, thoughts about the thing I was going to do next, and when I do that, what happens.”

“How much of that was legitimate in order to carry out the work? I mean, are the suggestions something that, if you don’t do them, you’ll find out by making mistakes?”

“I know from experience that I would have thought of almost all these things, but it was as if I had to go over it all in my head for some reason, they were coming back from association. About 10 per cent might have been useful. But the power was very strong, and I think I would not have seen that but for my efforts.”

“Have you finished that work? Will you be back at it this afternoon?”

“Yes. I have finished what you read out, but there is a lot more work there which I can go on with.” Gerry was here referring to how, after breakfast, Mr Adie would read out the work list, so that everyone would be aware of what was being done by others.

Mr Adie now suggested: “Then I suggest that you remind yourself each five minutes this afternoon, just for fifteen seconds. Time it from the watch. Fifteen seconds. Time that. And then begin again. You don’t leave it entirely, you return to it.”

The next question was from Paulus. When Mr Adie had asked a question at breakfast, Paulus had volunteered an answer, and something in him had been pleased when Mr Adie said: “Exactly”.

“There is essence-satisfaction in finding that one’s thought is right: that is quite permissible,” said Mr Adie. “But all these hands reaching over one’s shoulder to grab a bit of it … It is rather too difficult to understand that that actually robs me. I lose through that negative process. It can happen at any moment about anything. The whole education of eulogies and prizes … I can go all my life under that “education”, but if I could drop it by the end of my life it would be something, wouldn’t it?”

Part Two

Once it is stated, it seems so obvious that we need the impression of fatigue: without it, we would not know that we were tiring and would over-exert ourselves when it was dangerous. And when I receive the impression of my fatigue, rather than reacting with exasperation or rejection, the nature of the fatigue changes. But even more than that, my state changes, too.

I think this is the thing about Mr Adie’s endless stream of insights. It is not as if he heard Gurdjieff saying that we need the impression of fatigue. Rather, he learned from Gurdjieff how and why to change his state, and in a higher state, he sees very much more: including that we need the impression of fatigue.

Joseph Azize, 16 March 2018