Music of Georges I. Gurdjieff, a recording of a selection from Gurdjieff’s music, is played by the Gurdjieff Folk Instruments Ensemble, directed by Levon Eskenian. Issued in 2011 by ECM, # 2236, it takes an honourable place in the contemporary trend for Armenians and Russians to show serious interest in Gurdjieff’s achievements.

Gurdjieff’s writings and music are very often understood and interpreted as if they were Western European. This is hardly surprising. The last 27 or so years of his life were spent there and in the USA (with perhaps a short trip to the East), and at the time of his death he was, for most part, surrounded by persons of West European background. But just as the Bible bears many resonances and meanings only apparent to someone familiar with the ancient Middle East, so too, Gurdjieff’s music – or at least these more folkloric examples of it – come alive when treated as they are on authentic Eastern instruments by authentic Eastern musicians.

To my ear, this is the pre-eminent selection and recording of Gurdjieff’s Songs and Rhythms from Asia and Sayyid Dances. I wonder how Eskenian’s approach would work when applied to the Sacred Hymns, and especially the Hymns from a Truly Great Temple. I’m optimistic, and I do hope this CD will be succeeded by others from the Gurdjieff Folk Instruments Ensemble. Before coming to deeper issues, I deal with it track by track below, and the reader will see that while I am not much affected by some pieces, yet, the album as a whole has to be considered as something of a triumph. I would unhesitatingly pronounce it as superior, for purposes of attentive listening, to any of the piano recordings I have heard, de Hartmann’s and Rosenthal and company not excluded.

Track by Track

The opening track, “Chant from a Holy Book”, may be the most powerful piece on the entire album. The duduk is the chief instrument here. As Eskenian notes, its “warm sound closely resembles the human voice”. The playing is influenced by Eskenian’s view that the piece, as Gurdjieff wrote it, is in the style of the “tagh”, a sacred Armenian style of pre-Christian origin. As occurs so often on this CD, the use of different instruments adds a sustained dimensionality to the work which no other recordings have ever, in my opinion, captured. The scoring is such that one can clearly and distinctly hear and hold in one’s attention the several instruments and their diverse contributions.

The “Kurd Shepherd Melody”, is played on the blul, also known as the bilur or nayy, and accompanied on the saz, wind and string instruments, respectively. These instruments are actually used by Kurdish shepherds, and their use rendered the piece totally new for me. It strikes me as being chiefly of folkloric, not spiritual, interest, yet, it is of interest.

By contrast, the “Prayer”, played on “kanon”, an instrument much loved in the Middle East, has both elements. I have heard a lot of kanon in my time, and although I could be quite wrong, it seems to me that the playing and the recording here possess a virtuoso crispness and clarity. Yet, despite its technical brilliance and intrinsic charm, the recording lacks a certain impact. I would have to make much the same comments about the first two minutes of track 4, “Sayyid Chant and Dance no. 10”. However, when the “chant” gives way to the “rhythmic dance” (to use Eskenian’s terms), sparks erupt. The kanon seems capable of delivering a vivid sense of the folk tradition during this dance, but the more solemn pieces somehow elude it.

“Sayyid Chant and Dance no. 29” relies upon the nayy before the kanon and other instruments enter for the dance, and the effect is quite different. The entire piece has a nobility and grace, and the kanon does indeed deliver some poignant passages.

I was struck by Eskenian’s comments that the “Armenian Song” was in the manner of a love song, because if it is, it bridges secular and divine love, such is the impact it made on me. Again, it features the plaintive sound of the duduk.

When I read the notes about the different styles of “Bayaty”, and how their first passages were improvised, it struck me that perhaps when Gurdjieff demonstrated pieces like this to de Hartmann, he too, was improvising. This could account for the some of the difficulty of transcription which de Hartmann encountered. This was the first playing I have ever heard of this or similar pieces where I had the sense that the players were improvising as they played Gurdjieff’s music. Here, it is the oud which complements the virtuoso kanon playing.

It is difficult to record the oud well, but the engineers, Armen Yeganyan and Khatchig Khatchadourian, have pulled the rabbit from the hat, and enticed these delicate sounds to dwell in the digital. The rhythmic dance which follows that passage possesses a sweeping elegance.

Why, I don’t know, but “Sayyid Chant and Dance no. 9” fell a little flat for me. It isn’t that the playing is mediocre. It is perhaps that it follows several similar pieces with improvisation-like passages followed by dances.

“No. 11” from the Asian Songs is a welcome change. Eskenian rightly refers to its “mysterious” melody. The enigmatic ending, almost a fade out, is masterfully managed.

I had never liked the “Caucasian Dance” which is track 10 on this CD. But when it is rendered as ‘a version of a Shalakho dance” which leads into “the graceful, emotive solo dance, called siuzma”, the effect is utterly fresh. Having heard this, I now realise that the piano rendition had a flatness, almost a black and white quality. But this rendition uses a bright palette of tones and colours to make a fascinating piece. To me, this is not really a spiritual piece, but, still, it has brio and zest.

The next three pieces are, to use an already overused word, awesome. “No. 40”, again, from the Asian Songs, is a dream. This is one of those which I had never heard before the Schott edition. I was intrigued by the piano music, but this recording, with an Armenian ensemble is rather sublime. Also powerful, is the strange “Trinity” piece, played as an Armenian trio might, on “tar, sandtur and dap” (a drum also known as the “daf”). The more I have listened to this CD, the more this piece keeps at me: there is something in its insistent rhythm and graceful melody which reminds me of the music Gurdjieff produced for the Enneagram movement of the early 1920s, as if saying that the spiritual reality to which it points is ever-present, ever-flowing.

Then follows the “Assyrian Women Mourners”. The use of duduks and a dap is inspired. They combine solemnity, grief and dignity. The final note is sublime.

As with the “Caucasian Dance”, I had not liked “Atarnakh, Kurd Song”, the “Arabian Dance” or “Ancient Greek Melody” before hearing this recording, but I have been converted. The piano simply does not do justice to the music, but here they come alive. “Atarnakh” has a simple, graceful, almost hypnotic sway. I can now understand how it could have been written to be played before a reading from Beelzebub. It is transporting. The “Arabian” and the “Ancient Greek Dance” aren’t so forceful, meaning that the music doesn’t have the same power for me, yet, they’ve been rediscovered and revived, so to speak. Of these three, “Atarnakh” is by far the stronger for me.

Finally, the “Duduki” is one of the highlights, with the “Reading”, “Trinity”, “No. 40”, “Mourners” and “Atarnakh”. This double reed instrument all but speaks. Whoever the master musician is, his assured playing provides a fitting end to the album, allowing it to close, as it opened, with a powerful spiritual statement.

Presentation

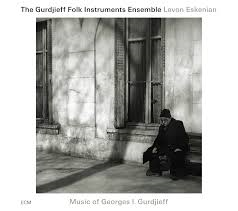

The CD is very nicely presented. It comes in a cardboard cover. Both the cover and the CD itself feature a good reproduction of that picture from Gurdjieff’s last years where he’s sitting on a bench by what is probably a Paris building, and a large tree shadow falls across the pavement and ground floor window. The back cover of the booklet, not the cardboard, quite appropriately shows Gurdjieff’s house in Gyumri, while inside the booklet, is an evocative picture of the roof and spires of the Sanahin monastery in Armenia. It’s a fascinating complex: one could fill one’s spare time with worse things than checking it out at this Armenian wiki site:

http://www.armeniapedia.org/index.php?title=Sanahin_Monastery

Closing Comments

The number of CD releases of recordings of Gurdjieff’s music has increased quite substantially, undoubtedly occasioned by the release of four volumes of much, but not all, of Gurdjieff’s piano music. Some of these recordings have used diverse instruments, and some have added words and singing of the interpreting artist’s own device. However, in my view, none of them, not excepting the soundtrack of the Meetings movie, have used Eastern instruments with the authority and success that Eskenian’s team does.

If I had to sum it up in one phrase, I would say that this album takes the Gurdjieff music out of the polite salons of Europe and North America, and rediscovers them in the distant, rocky and mystical East. I cannot help but feel that this is something Eskenian and his crew can be proud of. And I feel, if one can venture such a comment, that Gurdjieff too, would be proud, for he tried to link East and West by new lines of understanding. Eskenian is clearly sympathetic to Gurdjieff and his work. As the recording makes clear, he does not interpret Gurdjieff in a narrow Armenian manner, but is quite aware and respectful of Gurdjieff’s broader influences.

There is no point in repeating the many sound points which Eskenian makes in his liner notes. But one of them is critical, and presents an objective reason for interpreting Gurdjieff’s music using an Eastern ensemble: “ … these indigenous Eastern instruments are capable of producing microtonal intervals, rhythms and other nuances that are essential parts of Eastern music.”

I will not go into it here, but for me, these elements are all crucial in understanding Gurdjieff’s work. He was almost an engineer of the laws of the spiritual world. These laws are such that to us they are not laws as the laws of physics and chemistry are, but partake more of the nature of art, or even magic. However, this is an opportunity to provide some important material about Gurdjieff which is not readily available. Below I copy my transcription of some comments made by Thomas de Hartmann in an undated recording.

Thomas de Hartmann: “At certain points in space, where the emanations of the earth encounter the emanations of the Sun Absolute, that means, the emanations of the Almighty, at these points is a reflection, an image – a something which can be seen, assumed, felt, from the Almighty. And, for earth people, with concentration, it is possible to visualise, to see in a certain manner, inner, the emanations of the Almighty.”

“Of course, for this, a very great deep concentration is wanted. Here we understand why Gurjivanch put always a great weight on music. He himself played and he also composed, and he wrote down things, and so on.”

“If we compare the music of all the religions, we can see that music plays a great role, a great part in – so to say – religious service. but after the work of Gurdjivanch we can understand it more, that music helps to concentrate oneself, to bring oneself to an inner state when we can ?assume with greatest possible emanations. That is why music is just the thing which helps you to see higher.”

Levon Eskenian- Artistic Director

Biography

Levon Eskenian is an Armenian composer and pianist who was born in Lebanon in 1978. In 1996 he moved to Armenia where he currently lives. In 2005 he graduated from Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory with a Master’s degree in piano (class of professor Robert Shugarov). In 2007 he obtained his postgraduate degree from the class of Professor Willy Sargsyan. He has also studied composition, organ and improvisation classes at the Conservatory and harpsichord in Austria and Italy with the English organist and harpsichordist Christopher Stembridge.

Joseph Azize, 10 January 2012 revised 26 January 2017