Enchanting Modern: Ilonka Karasz (1896-1981), Ashley Callahan, Georgia Museum of Art, 2003)

The only disappointing feature of this beautiful book is that Ilonka Karasz’s status as a personal pupil of Gurdjieff is barely noted (see p.14). A quick check of Taylor’s Gurdjieff’s America discloses that she had joined Orage’s groups in the 1920s, married Wim Nyland (more widely known as one of the leading pupils, perhaps because he established his own groups), and studied with Gurdjieff both in Europe and the USA. I recall hearing that even after Nyland’s split from the Foundation, she continued to take groups at the NY Foundation. The little I have heard of her as a group leader has all been sincerely grateful. Having now read this book, and spent time in front of its beautiful full colour illustrations, it is to be perhaps regretted that her pupils have not produced a book about her as a teacher, because it is fair to conjecture that her approach to Gurdjieff’s ideas and methods would have the simple and dignified charm of her art.

Although it is a catalogue for an exhibition, this volume is, to employ the over-used word, interesting. The Latin word “inter-esse” means “to be in between”. Our fast and true etymological friend, W.W. Skeat tells us that the history of the word and how it came to mean “concerned in” is a lengthy one. So be it, but the word is ideal for describing the universal attraction to that area in between certainties, facts and givens. To be “interesting” is, in this sense, more than just to be curious: it is to be in that place where the third force can appear, to be poised to reconcile opposites, to bridge gaps, and to transcend the dead-end.

It is not that Karasz’s astounding variety of artistic output, from covers of the New Yorker, to textiles to silverware, manifests something divine. None of this art is on the same level as Piero della Francesca or Fra Angelico. Indeed, some of her art like the cubist influenced design on p. 50 is, to my eye, merely clever and well-executed.

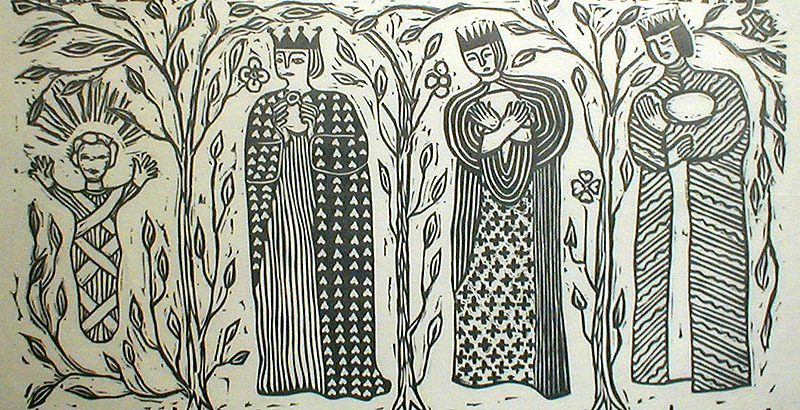

But there is often a sensitivity to living objects and to the life in nature which captures something, at least, of the “thusness” of reality. I think that this factor grew stronger in her work as she matured. At her best, something of the panorama of life is captured in a still, eternal moment, the way, perhaps, that Peter Bruegel the Elder does in his Children’s Games (1560). Further, the Christmas design reproduced with this review shows the clear influence of Gurdjieff’s sacred movements. Thus, a sense of the holy is mediated. Doubtless, it will mean more to someone who has worked at the movements, but still, there is a universality in these postures which anyone can imaginatively enter.

In much of her art, there is a sense of wonder, for example, see “The Flight into Egypt” on p. 24. There is also a sense of innocence, e.g. “Apple Harvest” on p.61. Sometimes, the wonder and the innocence are swept up in a quasi-mystical vision of the oneness beneath the diverse manifestations of life, as in “Ducks and Grasses” on p. 120.

That is, in presenting the “thusness” of the creation, something, at least, of its goodness, beauty and truth is also conveyed. I do not think that I am alone in believing that this can only happen where that goodness, beauty and truth have been felt and acknowledged.

So, what did I find especially interesting about this art?

Shortly, it so touched me, and touching me sparked such a chain of internal events, that I could not but ask: can art be an aide to the spiritual work? Of course, the answer is yes, but the fact that these productions prompted the question, stirring up my feelings, shows that the experience I had was fresh. Had it not been fresh, the question would not have been new. But it was.

And this in turn brought me to ponder something I had only ever seen out of the corner of my eye before: the way that there is an art, and sometimes a very fine one, in so many practices and professions of daily life.

I do not mean this in any trite sense: “We are all artists and our lives are our art.” This is not so. I cannot call art the wastelands of our lives, lived as they are with stormy emotion but so little feeling of my presence and reality.

Rather, I mean it in the sense that even when I was a lawyer among lawyers, there was a certain artistry in the best of our work. I was, for much of my career, a prosecutor. Sometimes a case would be prepared with such attention and knowledge, and such a concern for fairness, that the presentation of with carefully drafted and delivered submissions was indeed a work of art, perhaps on as high a level as the best even of Ilonka Karasz. I can recall, in particular, one elderly judge, possessor of both an excellent mind and a true sense of mercy. He would impartially hear the case and consider the evidence, then calmly proceed to judgment. It was like being in the audience of an orchestra caught up by sweet harmony.

Then, one can think of the liturgy. If Fra Angelico produced art fit for the worshipping spirit, perhaps the liturgy is worship which produces, for its manifestation, art which corresponds to a higher vibration. But only sometimes. For that exalted realisation, so much must enter in, not least the architecture of the church, the decorations, the music and so on.

I will leave with just one more thought: most of the art work in this book, and especially perhaps the artefacts, are not planned on a massive scale, or even a grand one. But they are, quite often, complete on their scale. Their simplicity and moderation corresponds to their theme, and vice versa. I have been pondering this question a good deal recently, thinking of how some pieces of music are a perfect ten, but only for what they are. Sometimes pieces are imperfect or blemished, but the ambition was greater. Both, I feel are needed. In Book VI of the Republic, Plato wrote: “All great attempts are attended with risk; ‘hard is the good’.”

That is sufficient for now. But again, considering this extraordinary little book confirms me in my view that good art seeks the morally and spiritually good. It serves beauty or truth – sometimes indirectly, of course – but in no other name can it advance.

Joseph Azize, 7 January 2017