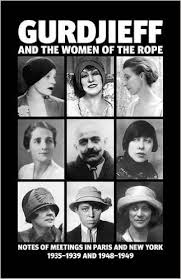

Gurdjieff and the Women of the Rope: Notes of Meetings in Paris and New York, 1935-1939 and 1948-1949, Book Studio, London, 2012

271pp. comprising a chronology from 1865 to 1935, covering the lives of Gurdjieff and the relevant women, notes for the years 1935-39 and 1948-49, with three appendices (1935 letter from Kathryn Hulme to Jane Heap, Hulme’s account of New Year’s Day 1936, and 1944 letter froGurdjieff and the Women of the Rope: Notes of Meetings in Paris and New York, 1935-1939 and 1948-1949, Book Studio, London, 2012

(271pp. comprising a chronology from 1865 to 1935, covering the lives of Gurdjieff and the relevant women, notes for the years 1935-39 and 1948-49, with three appendices (1935 letter from Kathryn Hulme to Jane Heap, Hulme’s account of New Year’s Day 1936, and 1944 letter from Janet Flanner to Solita Solano), a chronology for 1935-1981, and a drawing by Louise Davidson of “Mr G’s Kosmic Kite with Aspiring Astronauts”, and an index.)

This book has proved to be a surprise for me. When I purchased it, I thumbed through it, but being hard at work, put it aside. Also, I had read Hulme’s Undiscovered Country, the article on the women of the rope by Baker, Paterson’s book, which I considered a failure, and a photocopy of Solano’s typed notes. Someone said to me that there was nothing new in it, and I expected that would be right. I only picked it back up again, last year, in order to find some lines I remembered from Solano’s notes.

And I did find them. But I found a lot more, too. The anonymous editor transcribed the text of the book from materials in various libraries and collections, often puzzling over barely legible handwritten notes preserved only as microfilm scans of carbon paper. But the result is glorious: it goes so far beyond Undiscovered Country that it can be said to be the first sustained portrait of Gurdjieff teaching in that period.

When I realised the value of the fruit within, I began a programme of reading up to five pages each day, carefully, making notes. For two months or more, this volume was my companion over a pot of tea after breakfast. Completing that course of reading was like a friend after a house stay.

I have recently submitted a review of this volume for an academic journal, so I shall pass over most of which I deal with there. One of the formulations which Gurdjieff prized, and which I had not really grasped the importance of until this book, is his saying about not making an elephant out of a fly, or sometimes, out of a flea. I used to think: “Of course not”, but I had never seen that this was a trait which something in me was inclined to, until the striking way the idea is presented here made me question it, and then I saw that we all have a tendency to distort true proportion: we get worked up about what is actually trivial, and we barely notice what is really significant. I think the passage which really made me sit up was this one: it is May 1937, and Frank Pindar has joined Gurdjieff and the ladies for a meal:

Pindar: I want to ask you a question. I want to know why the French cheat one.

Gurdjieff: Now more than ever I can see which way you have gone, you ask such question.

Pindar: What do you mean?

Gurdjieff: Tell, Kanari.

Kanari: Elephant from fly,

Pindar: What’s that? What elephant? What fly? (p.157)

The book also contains the story, which I do not otherwise recall, of how in May 1937, Gurdjieff had parked a Buick on the side of a steep Alp, and alighted to admire the view, leaving a woman and some children inside the car. The handbrake suddenly slipped, and the Buick lurched to the precipice. “Never was my brain so quick”, said Gurdjieff, who had leaped onto the running board, reached inside and steered the car right into the only tree in sight. The passengers were saved, but the car was written off, and Gurdjieff, thrown high into the air, barely survived (pp.156-157).

Gurdjieff’s sense of humour, insight and wisdom come together in this anecdote. Gurdjieff has given them some “special liquor chocolates”, and Jane Heap, thinking to flatter Gurdjieff, says to him: “Every day in your house is Christmas.” Gurdjieff replies with this remarkable repartee: “Excuse! Twice a day in my house is Christmas. Look, Mees Gordon, she wish belittle me!” (p.57)

Women of the Rope is also important for showing Gurdjieff as teaching a series of inner exercises, designed so that although “born like dog, die part of god” (p.5). I have dealt with that in the academic review.

Many of the comments attributed to Gurdjieff sound as though he could have been quite serious, but still, they are of no use unless we ourselves can understand what they mean, and how they are true. For example, Solano writes, after a reading from Meetings with Remarkable Men: “Last night Gurdjieff told Alice that the last three portraits in his “gallery” = Karpenko, Dr Elim Bey and Skridloff, from which three full books will flow, represent the astral body of man” (p.58)

Is this so? And if it is, what use can we make of it? Gurdjieff did not in the end write three full books based on these characters. Did that mean a change in what they represent? But if I read the book with an interest in that question, I start to see it differently.

The book has a profusion of fascinating comments, reversing our assumptions: once more, what do we make of lines like this: “If beautiful face have man or woman, always I know is merde (i.e. shit). If lawyer or engineer I need, never I choose beautiful face – merde is. I choose monster. He is not spoiled. He study when young, is clever” (p.190).

That made me feel a little better. This one, commencing on the same page, relates more directly to inner work: “Man is man. He cannot be otherwise. He is such that he can never change his body. He can only be as he is because he is the result of heredity. But his mind he can educate and with this control his animal body and not be its slave. He must at all times struggle and his mind grows stronger, so will his weakness grow stronger. This is good thing, it makes for more struggle. It is not good if body at once lies down. He must command, he must direct” (pp.190-191).

It is hard to express how much the effort of having to work through Gurdjieff’s terse English pays dividends. If we let the nuggetty style turn us off, we sleep walk through gems such as this: “I make another vibration from these ordinary things (his cooking, music and Christmas tree). Truth, after look long time at this tree in beginning of new year, you can have food for whole year. Man can look and not be just animal. When once you are initiated for one thing, it is like chain – one link flow to another. And then whole chain flows” (p.184).

And then, what are we to make of this? Gurdjieff is telling the women that: “Nobody now believe in Christian thing, not with inner world, especially young ones. Nobody but English old maid and your American lesbians. In general, man over there not believe” (p.156). Does Gurdjieff mean it, does he not, or is he just putting it out there? The question is a real one, because he was addressing an English old maid and some American lesbians. Is he saying that they do believe, and that they are right to? What does he really mean by it? And is he not, in the final analysis, telling us about how he sees his mission?

I will close with a prize: “I will give you a program for living so you will know how to live in inner life. You must remember when you feel bad you must not lose yourself with mind. Some days you feel bad, then with swing of pendulum, you feel good. On your worst day, prepare for best day. This is the law. What is important is that you never lose self. Let mind be big sister to take care of little sister who is now in the house. Your nature is your little sister” (p.66)

One question arises, though: I wonder if he actually said: “On your best day, prepare for worst day”? Still, if one ponders it both ways ….

Thanks Joseph. This article prompted me to restart ‘Undiscovered Country’ which I recently finished, and further, to begin reading ‘Gurdjieff and the Women of the Rope’. Undiscovered Country was the first of this type of account (biographical with G.) I had read in some years and found it a worthwhile read.

I’m now looking forward to getting into ‘Gurdjieff and the Women of the Rope’ and like how you added a small task to the reading (6 pages per day and notes). I’ll add something similar.

“ One question arises, though: I wonder if he actually said: “On your best day, prepare for worst day”? Still, if one ponders it both ways ….”

I haven’t yet got there to read any context etc but I have a sense it’s right as stated in the book, you don’t want to over spend on your best day knowing a recession is around the corner. That would provide a very worthwhile activity to work at during those difficult days which would be helpful in the longer term. Do what it doesn’t like…

W.

I, too, was surprised. It was hard reading at first when it just appeared to just be a diary, but then it unfolded into giving insight into Gurdjieff’s teaching techniques: the merging of everyday living into the practice of developing and ‘I”. Crocodile and Canary were well matched.